A chaotic journey across half the planet by train — where bad planning collides with blind luck and sheer stubbornness keeps the story moving.

Chapter Two: Mongolian Train, Chinese Caboose

Finally we are on the train. I haven’t been on an overnight train since my family tried to make a National Lampoon Holiday trip on an Amtrak transcontinental crossing in the late 70s. Chevy Chase would have been proud. Five kids, a cramped couple of cabins and totally incompetent Amtrack management had all the right ingredients for sophomoric comedy. Baby brother Sean, who didn’t start speaking until an alarmingly late age, found some amusing ways to mangle the English language. “Where did the quarter put our stuffle bag?” has become family legend since that trip [translation: “Where did the porter put our duffel bag?]. So we stuffed him in the duffel bag for a half hour or so while our parents were in the bar car. He didn’t mind.

Our train, by contrast, is a Mongolian run train. Judging by the stern looks of the stout, all-women train attendant team, Amtrak nonsense will not be accepted. If the IOC ever bring back rugby to the Olympics, the Mongolian National Train Service should consider fielding these women as a team. Bronze! at the very least. And that’s assuming they enter the men’s competition.

The train is clean, very comfortable and efficient. After twenty hours we decide we like the leisurely pace of train travel. There is a subconscious comfort in the steady swaying of our cabin together with the metronome beat of our steel wheels thumping over the tracks. The train is not crowded. Perhaps because of this even second class, with 4 berths per cabin, looks almost luxurious. Travellers seem to be a pretty even mix of Mongolians heading home, Chinese traders and European backpackers. It seems that the only other people in the 1st class cabin are Mongolian. Definitely no (other) backpackers.

There is a lot we don’t understand from our assigned matron. She doesn’t speak English or Chinese (or French for that matter) but she does spend a lot of time making delicious looking stir-fried mutton noodles and juicy dumplings. She starts delivering them to the cabins furthest from her little cooking niche at the front the car. Our cabin is furthest forward, next to her station. But nothing is delivered to us. We wait. When we can no longer detect the promising smells of lunch, I peak around the corner and see Madame settling into a book. The kitchenette is spotless already. This food is clearly not for us. We hope there is a dining car.

We are just about to give up when finally we locate the dining car. I’ve looked everywhere and even stumbled into the back end of the locomotive in my search. The dining car travels at the end of the train in what I recall is the caboose position. What an odd word: caboose. I must look it up some day. I suspect there is a story behind it. We sense immediately that there is something different about the caboose. It’s a bit dirtier, somehow chaotic and it’s staffed entirely by men who are now gathered around the end table, smoking cigarettes and drinking strong tea from stained shot glass sized cups. They are loud. And I understand a bit of what they are saying. Finally, we figure it out: the dining car is Chinese. And its caboose situation is probably intentional. Everything about it can be summed up in one word: afterthought.

The menu is six dishes long and it’s written by hand on the back of an onion skin order sheet pad. Five of the dishes are chicken based, the sixth is eggs with tomatoes. The oldest street dish in China and reserved only for the laziest Chefs. For 2 kuai you can add on a bowl of rice. It’s the worst rice I’ve ever had. It’s not the fault of the grain. This stuff has been over cooked in too much water and left standing for several days, I am sure. It’s the kind of stuff that probably inspired the invention of wall paper. If you had to figure out how to get paintings to stick to a wall, this is the stuff you would start with. Fortunately, the chicken dishes aren’t bad. But the most annoying thing is that they still don’t seem to understand my Chinese. And this will be my last chance to try to use it.

In the morning the Chinese Caboose will be gone. It will be replaced by a Mongolian dining car located in the middle of the train, one car ahead of us so only about 15 feet from our cabin. This is what I expected from 1st class. It will be run by women who are serious and efficient. It will be clean and have its own sound system to play dreadful western pop songs. The menu will have more than chicken on it and the blini-like pancakes will be delicious. The rice will have been cooked within the present decade.

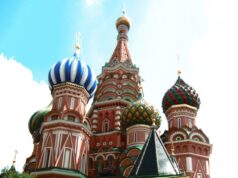

We reach the border crossing just before midnight and here is when the railway staff starts to get busy. It’s not about handing out immigration forms, preparing the cabin for descent or the other preparation you expect prior to arrival. This is a complex and collusive game they run with a few Chinese traders and the odd male Mongolian railway staff. Boxes and bags of merchandise are shifted around from one cabin to the next, put into lockers and removed. A few hand radios are involved in giving instructions. We see the same 20kg rice bag moved in and out of three different cabins and a couple of toilets. It’s a huge shell game of some sort and by this point we conclude the rice bag probably has more than rice in it. It looks like it weighs more than 20kg too. Chinese immigration and customs staff start wandering about and collect our passports. They look through closets and open toilets. They even help us discover that there is storage space beneath our lower bunk. They don’t come away with any suspicious rice sacks though. Chalk up one point for the Mongol – Chinese Smuggling team! This success has a decidedly positive impact on our matron’s outward demeanour for the rest of the trip. We catch her smiling a couple of times and the next morning she will even bring us a few small plates of the dumplings I purposefully eye whenever I see her preparing them for the Mongol VIPs in our cabin.

Amidst all the smuggling commotion we somehow miss the information that we can get off the train here in Er Lian for the next hour. Instead we remain captive while the train is rolled into a huge warehouse and the under carriages are exchanged for the wider (or narrower?) guage tracks on the other side of the border. We roll a few kilometres down the track and the Mongolian customs officials come aboard. They are quick and efficient and seem to make a special point not to look in any storage spaces or under our bed. It’s around now that it occurs to us that we have done appallingly little planning for our next stop Ulaan Bataar. We don’t have a hotel reservation. We aren’t sure what time we arrive. We don’t know the name of the local currency, let alone its exchange rate to the dollar, renmenbi or euro. The guide books we have downloaded turn out to be something entirely different and completely useless. All we know is that we have two and half days and want to see a bit of the country side. Maybe stay in a Ger. It’s this kind of planning that will prove if we are hopeless travellers or creative ones. In the meantime, I’ll send an SMS to the only two people I know who have been to Mongolia. Hopefully they have at least the name of a hotel to look for.