A culturally insensitive, politically incorrect and historically inaccurate account of trekking in the Hermit Kingdom.

Chapter Seven: Regrets Descend

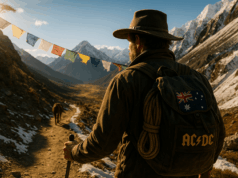

We still have a day and half up here. There are worse places in the world to be stuck. The other guys want to see the lakes and the pass. It’s a great walk and I don’t mind doing it again. At the end of the valley, they see the snow and everyone agrees it is formidable. Then we spot two small dots up in the pass approaching the point I got to yesterday. Ben pulls out binoculars and confirms that they are human. They move much faster than I did but I figure this is normal since the guide, Dzambo and I cut a decent path with all our stomping and tripping. Then they continue well past my high point and disappear out of sight up the pass. They haven’t slowed down at all. This is outrageous. I am offended and hurt. And why are they continuing through the pass at this time of day? It will be too late to get to the next camp site even after they come down out of the snow line on the other side.

Bagger, Ben, John and Roger all want to touch the snow line. I am not interested in walking the narrow slippery path. The beginning of the pass is the most dangerous. So I retire to a yak herder’s enclosure where I can get out of the wind and tap out a few notes on my i-pad.

In these seasonal grazing areas the herders build semi-permanent stone structures to put their tents on. Flat stones from the mountainside are expertly slotted together with no mortar, dry or wet, in a square about waist high. When in residence, the herders pitch their heavy woolen tents on top of the stones. It’s a brilliant system. The stones block the wind and tent fends off the snow or rain. In the center of the enclosure more flat stones are arranged like a sacrificial alter. Soot and burn marks suggest it’s probably used as a heat source. But I can’t figure out how the herders have built a fire in this odd shaped contraption. It’s seems too small to hold anything but kindling. And then I realize that there isn’t a scrap of wood for miles. Of course! They must burn dried yak dung. It is designed to burn little piles of excrement.

Bagger is back now and he confirms that the initial ascent is dangerous and slippery. “And my shoes really do suck” he continues. It’s a long steep slide to the lake at the bottom of the hill. A slide no one is likely to survive. The path and steep drop resemble a spot where a young hiker tragically died in Norway on a school trip Bagger took a lifetime ago. “We should have been tied together. Imagine having to tell the parents” he says.

“Were you tied in just now?” I ask.

“Uh……No. Good point”, he concurs. “Let’ get the fuck out of here”.

We all head back at a leisurely pace. Ben stops occasionally to look back at the pass. Suddenly he calls ahead “those guys are coming back!” We slow down, find a sunny spot out of the wind and wait for them.

This is a mistake.

“Did you just go across the pass and come back?” I ask.

“Yes, of course. Much snow!” he says. We can’t quite place his accent. It sounds vaguely Italian.

“Where are you from?” the Philospher-Cynic asks.

“Bhutan, of course” he says and looks at Bagger like he has just discovered the village idiot.

He is the guide of a huge 19 person group that arrived at the base camp last night. He is the only guide for this group. His companion is their head horseman. The horseman looks exhausted and has claimed a seat on a nearby boulder as soon as his boss stops to talk to us. “This guy even tires out the horsemen!” I think to myself in an incredulous, jealous and very impressed sort of way.

“So are you taking that group across the pass tomorrow?” Ashley Gideon asks.

“Yes, of course” he says.

“But some of those people look rather old?” Gideon counters.

“Yes, of course. One is 72 years old”.

“And you are still taking them across!” John asks.

“Yes, of course.” Now we think he is mocking us with this ‘Yes, of course…’ routine. He is leaving unsaid the rest of the sentence: ‘Yes, of course… And why aren’t you? … Are you soft?’

He continues, “They really want to go. So today I take a look at the whole pass and make a track. I will tell them when we go that there is no turning back. No Plan B”. He really says this. We can’t believe it.

All we can do is follow him back to the camp in silence. But we can’t even do that very well. Within five minutes he and his horseman are out of slight as they bounce down the steep switchback trail not even bothering to look where they place their feet.

The regrets are descending on our thoughts now. Why didn’t we fire our guide as soon as he told us he didn’t like Chilips? Why didn’t we all go to look at the pass on the first day? Why did the others listen to me? Why was I so uncharacteristically risk averse? Why didn’t we go back to Nepal or to Patagonia instead of Bhutan? Why didn’t we take the longer route? Why did we waste so many days doing culture-tourism crap in Trimphu and Paro? Why are we such wimps? Why didn’t Ashley Gideon save us from our own cowardice?

This is what the Philosopher-Cynic meant. Now I understand. It’s important to consider the paths not taken. I hope he is right about the “Regrets build character” part. I am still waiting for the character building to begin while I lick psychological wounds back in Bangkok.

Ben is already thinking ahead. “If we do this again, we better not wait 9 years. Do you realize how old you guys will be in nine years? “

Thanks Ben.