A culturally insensitive, politically incorrect and historically inaccurate account of trekking in the Hermit Kingdom.

Chapter Six: Decisions at the Bhong Te La Pass

If John, the 2iC, is over-prepared, Bagger is under-prepared in equally impressive amounts. This is not unusual. He likes to confirm attendance at any event only at the last minute. It is touch and go up to the moment of departure but he usually shows up. He never reads itineraries until he is at the airport. I am sure he has never read the assembly directions on an appliance he has purchased until it is set up, not working and he has just noticed that there are five mysteriously unused bolts in his left hand. On this trip he had to get from Sydney to Bangkok by 4am on a Thursday. Luckily he called me on Wednesday asking what time on Friday he needed to arrive. All the information was in the itinerary he received four months ago. “Oh, I guess I better find a flight in the next few hours”, was how that conversation ended.

He will show up to a trek with only two pairs of socks and one pair of long pants. But he never complains about his own missing gear and he still manages to lead the group on most days. This is why it is strange that he did not come with me to check out the high pass.

Our trek, like all others to this region, was designed to come up to the Cholomhari base camp where we would hang around for one day and take in a local hike or two. The next day we would cross the 4,800m (16,000ft) Bhong Te La Pass. From the trekkers we passed on the way up here, we knew it had not been crossed since a low pressure system dumped some unseasonably early snow on the mountaintop. But we also knew there hadn’t been any new snow for the past few days. Every night and every day was occupied with discussion on what our options were. Could we get a few yak herders to drive a herd across the path ahead of us? Could we get out by another pass? How much would we have to pay if a few ponies didn’t survive the crossing? Did we have enough food to take the longer 12-day route out? Could we change our return flights if we did that?

Finally we did establish one viable option. It would be possible to send the ponies around the mountain to meet us on the other side if we could at least cross the pass by foot. Our guide was very non-committal on the prospects of a successful hike through the pass. Suddenly he was very Zen: “We shall see when see”, was all he would offer. Later we learned his plan was to head up to the pass with the head horseman on the ‘rest day’ while we took in a local hike. He would let us know if it was doable when he got back to camp in the afternoon.

We didn’t trust him. We believed he would walk to within a couple of kilometers; see snow and turn back to camp with bad news. So we decided that Bagger and I would accompany him and the head horseman to see the situation for ourselves. Inexplicably, and completely out of character, Bagger decided not to go with me on the designated morning. He had a bizarre twisted logic for this decision that I couldn’t be bothered to ponder. So I was left with the guide and the head horseman. The guide didn’t want to have anything to do with me. He tried three times to convince me to follow the others and leave him to his work. Finally, he relented and off we went, late as usual.

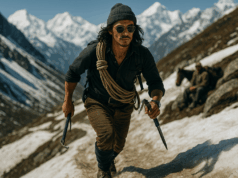

It is a two to three hour hike to the beginning of the Bhong Te La Pass. The hike starts up a very steep switch-backed trail that will provide commanding views of the camp, Chomalhari and Jichu Drake from its top. Down at the start of the path, the guide tells me he has to take a piss so I should follow the horseman. The horseman, evidently just as pleased to be rid of the guide as I am, dashes up the path. He is in his element now and moving fast, faster even than Bagger. At the top we look back down the switch-backs. There is no sign of the guide. We do see the Danish lady who has recovered enough to make it a third of the way up the path. So we carry on up the glacial valley towards the pass.

I finally learn to pronounce name of the head horseman, who is now having as much as fun as I am. I think he likes being away from the responsibilities of the ponies and the camp. He skips flat stones across the mercury smooth surfaces of the lakes. He points out trout hiding in the algae. When we see a herd of blue sheep making a crossing at the lowest part of the valley floor, he bolts up the hill to set an ambush. The wild blue sheep are not blue at all and they look more like rams than sheep to me. They typically stay uphill of anything that might threaten them, like a crazed horseman. This is why Dzambo is so excited. They are below us.

He tells me later through pantomime and a handful of English words that if he gets above the blue sheep, he can charge the herd while throwing sharp edged rocks at them. With a bit of luck he will stun one with the rock and then slit its throat with his blade. I think this is bullshit and dreadfully non-PC. But this is his country and I am not one to judge. It’s fun to watch him try and fail. And it’s impressive to see a guy run at full sprint, uphill at an altitude of over 4300m. There may be some small credibility to Dzambo’s bold claims. Like all the other horsemen, he carries a mean looking 20-inch blade in a wooden scabbard. I have no doubt it could be used to dispatch a blue sheep or even a Roo for that matter. I am sure Dzambo could earn his keep at Ben’s farm.

It takes us almost an hour to get to the end of the valley even though it’s only a 4km walk. We stop for tea, biscuits and a Snickers bar next to a sun baked blue sheep skull. Finally the guide shows up and now he is seriously furious. “This is not funny! This is not a race! It is not a competition! It is high altitude and dangerous! Didn’t you hear my whistle? Why didn’t you wait?”

I honestly didn’t know he had a whistle. The wind roars down the valley in the direction we are walking and its cold enough to warrant a beanie under my cap. So, no, I did not hear the whistle. And it probably would have made no difference if I had. So I tell the guide “Dude! You told me to follow the horseman so I followed the horseman!”

He doesn’t know how to respond to this. So he launches into a Bhutanese tirade against Dzambo. I assume he is saying much the same thing. I swear Dzambo eyes are laughing at him. Right there I decide that if we ever get into trouble up here I am following the horseman not the guide.

The guide settles into a grumpy silence after we pour him some tea. We quietly contemplate the pass in front of us. Ahead is the last of three pristine glacial lakes at the end of this boxed valley. The end of the lake is framed by a massive amphitheater shaped cliff several hundred feet high. Somehow, we are supposed to get to the top of that. It is impressive and it is indeed covered with snow. The path from here traverses the scree strewn mountainside to the left lake. The trail is about 8 inches wide, muddy where there are no bands of snow and very slippery. I have forgotten my walking stick at a time when I finally need it.

Now beyond and several hundred feet above the lake’s elevation, we are entering the snow line. The snow is waist deep. Each step requires a deep breath and a ridiculous amount of effort. The snow has melted and frozen often enough that there is a crust at the top. At every third step I am likely to plunge a boot through the crust filling my pant pockets with snow.

But it is not impassible. At least not for humans. No Pony will make it through this stuff. I am told that if the snow is above a pony’s knee, it can’t lift its leg high enough to make forward progress. We make steady if laborious progress and reach a high point well above the center of the valley and the last lake. Ahead, we can see to the end of the pass. It will be no more difficult than what we have covered so far.

It’s a quiet walk back until Dzambo gets bored again. At the steepest part of the path above the lake he sits down behind an enormous boulder and uses two legs to shove it down the hill. It turns once, twice and then goes tumbling 60mph down the steep grade towards the calm lake below. The guide delights in this. In a rare moment of playfulness he scampers across the hill with Dzambo looking for boulders large enough to attain terminal velocity but loose enough to pry from the hill without pulling a hamstring. I can almost forgive his petulance as I watch and film this delinquency.

It has been a long day by the time we get back to the camp. The guys are in the mess tent. The guide gives his report and it surprises me. “It’s probably possible without the ponies but not advisable”. He mentions avalanche risk, our lack of proper footwear and frostbite. “But it’s up to you guys. If you want to risk it, we can go.” Then, even more surprisingly, he leaves us so we can contemplate tomorrow on our own. We go tomorrow or we stay another day and head down the broken path we arrived on. This is all we have for Plan B: Retreat. We must decide now.

I tell the guys what I have seen. I show them the pictures and video I have taken. To my surprise and great regret I find that within moments I am the one recommending that we give up. I hadn’t even made a decision before I started talking. Why is this coming out of my mouth? It is like someone else is speaking for me. Someone smarter and wiser, perhaps. I had been told on several occasions before I left Thailand “Not to do anything stupid!”. It is an established fact that I am prone to both stupidity and accidents when I go on any kind of tour with these guys. Why should a trekking tour be any different in this regard than a golf tour or a tour to watch a rugby match somewhere far away? But this is ludicrous. I came here to push myself and the best I’ve done is walk alongside a 7 year old with her own pony.

It is decided now. The decision is based largely on the only credible account of the conditions: mine. No one is happy, except the guide when we tell him that we will retreat. I sense that Dzambo is even disappointed in our cowardly choice. So we finish off another bottle of whiskey, have dinner, play cards and head to our tents. It is a schedule most commonly found in retirement home.