A culturally insensitive, politically incorrect and historically inaccurate account of trekking in the Hermit Kingdom.

Chapter Four: Becoming Ashley Gideon

Roger takes up the role of Ashley Gideon for the remainder of the trip. He does this with dedication, expertise and fair amount of élan. He and John, also an ex British Gurkha, are the only ones who shave during the trip. They explain that this is simply one of the many things that officers do to maintain discipline and morale. But Roger is leaving mutton chops behind and by the end of the trip is starting to look the role. Ben and I are happy to be the grunts in this equation. It is way too cold to bother shaving. Bagger doesn’t have to worry about it. At 50 years old he still can’t grow facial hair.

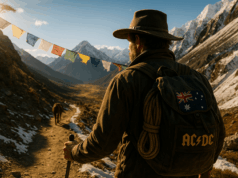

Roger is settling well into his role as Ashley Gideon. It is an appropriate part for him. He is our organizer for this trek as he was for the Nepal trek we did nine years ago. If there is a decision of any consequence to make, we generally defer to him. He is more than comfortable taking command and we are more than happy to follow his (or Ashley Gideon’s) authority. He has a background story that could just as easily have been written in the mid-1800s as it was at this turn of the millennium. Raised by a British Gurkha officer in a picturesque corner of Gloucestershire where you wouldn’t be surprised to see a few hobbits down at the local pub, Roger did his time travelling the world aimlessly after school. He eventually found himself at Sandhurst where it took him two years rather than the traditional twelve months to graduate. Tours in Nepal, Brunei and Hong Kong followed before the Gurkhas were reduced in size to a single regiment.

Other than his colonial bearing and ease with which he takes command, one particular fact gives Roger the un-questioned right to take on the persona of Ashley Gideon for this trip. Roger is the only one of us who has a name card that reads “Governor General”. The details are murky. But he somehow ended up being appointed the Governor General of a little known appendage to what is left of the British colonial system in the Caribbean. This gets him invites to pretty awesome parties like the one at Buckingham Palace a few years ago for a notorious wedding. With the mutton chops slowly filling in, there is no question that Roger is Ashley Gideon for the duration of this trek.

The only downside to being Ashley Gideon is that he has to deal with reports of our alleged misbehavior from the guide. It takes three days to get to the Cholomhari base camp where we will remain for far too long. In that time the reports are numerous.

At the base camp, John and I chat with a Danish woman who arrived shortly after us. She is experiencing the early stages of altitude sickness. She says “Oh! You are the group that is causing all the trouble!” She sees the confusion on our faces. We can’t imagine what she is talking about. Perhaps Roger, who traditionally commands from the rear of our column, left a distinctly human turd amongst the endless piles of pony shit for her to step over? Before we feel obliged to offer unpleasant theories involving Gurkha scat, she rescues us and continues: “Well, our guide says that your guide says that you guys are creating all sorts of problems for him. You walk at different speeds, you don’t want to stop at the same places he does and you don’t listen to him.” Most of this is true. Our variable speed strategy is partly designed to confuse him. The truth is that no one wants to walk with him. If we spread out then he gets confused and tired. Eventually he sulks on his own somewhere near the middle or end of the column which can stretch for several kilometers when we get it right. We don’t want to stop at his well-worn lunch spots because they are filthy. One hundred meters in either direction there is generally a beautiful, pristine and hardly used place to stop.

John continues chatting with the Danish lady while Roger retires to write dispatches to The Regiment in his tent. Ben, Bagger and I wander up the valley away from the trash around the camp site. The litter is starting to depress Bagger and he is depressing us by talking about it so much. The guide tells us there is a village up that way where we can buy beer. He is lying to us. He just wants to get rid of us. We only come across a couple of sturdy houses with yak enclosures being prepared for the winter. The homes look entirely private and we don’t feel it is appropriate to knock on the doors asking for beer that might have taken five days to get here on the back of a pony.

Further up the valley we run into three guys swaddled in green military looking outfits. Only their faces poke out from their tight wrappings. They look a bit like military versions of those Russian Babushka dolls. They are heading down from higher passes. They explain in remarkable English that they are with the forestry department not the paratroopers, which was my best guess. They are part of a six year program to catalogue all the flora and fauna of Bhutan through random sampling. Teams like this are spread out across Bhutan carrying GPS devices pre-loaded with the randomly selected coordinates for investigation. They hike around until the GPS unit alerts them that they have arrived at the pre-selected coordinates. They stake off a 12 by 12 meter square and then count everything living in that space. These men have patience and dedication.

Inside are 3 generations of women. There is the grandmother, a young mother and a baby who can’t yet walk but is content to crawl around on the sooty floor pausing only to stare at Ben in astonishment. There is no beer but they are happy to offer us yak milk tea which is warming on the dung fueled brazier. We are well above the tree line so fire wood is hard to come by. Dried yak dung seems to work well and doesn’t smell even remotely as I imagined it would. It is piled up on stone walls around the houses in monumental portions to dry. The Rangers encourage us to buy a length of hardened yak cheese. It is dried on a string in rectangles the size of matchboxes. I have no idea how it can actually been eaten. It is very hard. It might be easier to eat an i-phone. But the Ranger dudes tell me it can sustain me for days in an emergency so I buy a string and put in my pack. Since an emergency is very unlikely, I know it will look good hanging in the kitchen somewhere when I get back to Bangkok.

The Rangers and the women are all delightful company and gracious hosts. We see this everywhere we go in Bhutan. There are less than 700,000 people in Bhutan and everyone we have met, with one notable exception, is pleasant and engaging. It seems we have somehow managed to be guided around by the only disagreeable person in all of Bhutan. At some point along the way, we learn that he is half Tibetan. I have never heard ill words spoken about Tibetans. I’ve never been there. And I guess we are conditioned to pity the Tibetans on account of their dreadful subjugation at the hands of the Chinese. But perhaps the acrimonious history between Tibet and Bhutan, even if ancient, makes it tough to be half Tibetan in Bhutan and still be a nice guy.